In 1953 the brilliant systems theorist and cybernetics expert, W.

Ross Ashby noted: “Only variation can force variation down”[1],

which he published in his 1956 book An

Introduction to Cybernetics as The Law of Requisite Variety: “[only]

variety can destroy variety”[2]. To put it another way, “control can be

obtained only if the variety of the controller … is at least as great as the

situation to be controlled”[3].

Variety is the number of distinguishable items or states[4],

so if you’re in a situation where there are 100 possible states, you can only

effectively deal with it if you can mimic those 100 states yourself: you have

to have the same variety capacity, otherwise you simply can’t deal with all the

variety you encounter. Of course in reality the amount of variety we encounter

is far greater than this: possibly almost infinite. Stafford Beer, another

brilliant cyberneticist, took Ashby’s work and built a model for how to deal

effectively with variety, which he called the Viable Systems Model (VSM: of

which more later). Basically, Beer stated that in real life it’s impossible to

match variety 100%, so the controlling system needs to be able to deal with

variety in such a way that it remains viable as a system (i.e. it can survive).

He called this requisite variety.

What has this got to do with projects and project

management? Putting this into project management terms, a project can only

successfully deliver if it can deal with the variety it encounters effectively.

If this sounds like common sense, so it is. But how do you do that. How do you cope with variety

effectively given that you can’t deal with it 100%? Beer’s VSM is all about

having a model that can understand enough about the variety to deal with it

effectively, without being flooded with all the variety that there is. And to

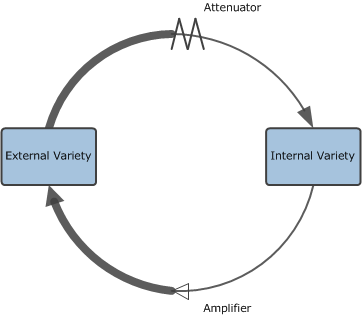

do that you need some kind of filter (Beer calls this an attenuator) so that

the incoming variety is reduced. You also need an amplifier on the output side

so that your output isn’t just lost in the noise of the variety that’s out

there.

To use a very simple

human analogy: we filter out background noise in a crowded room so we can

listen to the person we’re speaking to. How does our attenuator work? We make

sure we are looking directly at the person we’re speaking to so we can pick up

visual signals to help us filter auditory input. They help by amplifying their

output to help you focus on it, for example by saying your name to help you

“pin” their speech. They might write something down or draw a diagram. And so on.

So now we have a basic model of how to deal effectively with

variety, as illustrated here[5].

However there are four problems that I believe commonly occur in projects that cause this loop to fail somewhere:

However there are four problems that I believe commonly occur in projects that cause this loop to fail somewhere:

1. Putting attenuation in the right place

One of the biggest problems with projects is getting the

attenuator and the amplifier right, and there are two issues here. The first is

getting them on the right side of the loop – as shown in the diagram. Often we

do the reverse and have the amplifier on the incoming route – making our

ability to deal with variety worse, not better; and the we attenuate the

output. Let me give a very simple example. We gather requirements for a system.

An awful lot of them. We talk to lots of stakeholders to get their points of

view. We get a lot of those too. Some of them are in conflict. But we strive to

“gather all the requirements” (amplifier). Out of this welter of

incoming variety we create a product of some sort, but we fail to engage fully

with the customer (attenuator) so it’s never fully deployed. The recent article

by Mark Phillips in PMT had a great example of this with a development project

that failed because the scope kept increasing (amplified input)[6].

So the first thing to do is make sure you have attenuation in place on the input side of the project. Next we’ll look at how this should be configured so you cut out what isn’t necessary but don’t cut out important stuff.

So the first thing to do is make sure you have attenuation in place on the input side of the project. Next we’ll look at how this should be configured so you cut out what isn’t necessary but don’t cut out important stuff.

2. Getting attenuation right

Assuming we are attenuating the input, how do we do it

correctly? In DSDM Atern the use of MoSCoW[7] is recommended to prioritise requirements: MoSCoW can be an effective

attenuator if use correctly. However, in spite of tools like MoSCoW and

methodologies like DSDM Atern, we still seem to get it wrong too often. This is

sometimes because the attenuation is not effective (e.g. people don’t

prioritise effectively: everything is a “must have”).

Another attenuator we don’t use effectively enough is

stakeholder management. A good stakeholder analysis will reveal those

stakeholders who will have a lot of power and influence over the project, and

also those who may not be so powerful but will be key users. We can then

effectively ignore all other stakeholders in terms of getting input: we don’t need

to know what they want!

Sometimes the attenuation works fine and still the project

fails! This can be cause amplification isn’t working properly, as we’ll see

next.

3. Getting amplification right

A third problem is ensuring that the output is properly

amplified assuming the product is completed effectively and the input side of

the loop is OK. A typical example of poor output amplification is when a product

is successfully delivered – and then is either not adopted or not effectively

adopted. This is very common in IT systems implementation where the grand new

system ends up causing more problems than it solves because staff don’t like it

and find workarounds. Often there is insufficient work done to prepare people

for the new product so their expectations are misaligned with what is

delivered. This is poor amplification on the output loop.

Typically we use communication methods such as emails and

posters and web sites. But these can get lost in the noise: they aren’t effective

amplifiers. We need to explore what the users will take notice of and use

those. This will differ from one situation to the next. One very successful

project I was involved with, where schoolchildren were the intended users, created

a piece of live, interactive drama that was delivered to the schools, and this engaged

attention and got a good result.

4. Dealing with internal variety

The diagram also includes the box on the right side of the

loop – the actual project itself. Will the project deliver its products

effectively, even if we get attenuation right? Often we fail in this too, and a

big contributor is that we don’t treat the project as a system. Beer’s Viable

Systems Model is a generally applicable model for the cybernetic organisation

of how a system should work. Projects are systems, so the model can be applied

to projects as well. I have written a series on this topic, the first part of

which you can find here.

[1] See the Ashby digital archive, and page 4659 of his Journal, available online at http://www.rossashby.info/index.html [Accessed 19 October 2015]

[2] Ashby, W.R. (1956) An Introduction to Cybernetics, Chapman & Hall Ltd, London, p. 207

[3] Beer, S. (1972) The Brain of the Firm, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, p. 41 (2nd ed 1981)

[4] ibid

[5] Based on a diagram used by Stafford Beer in his 1973 lectures Designing Freedom, available online at http://scio.org.uk/sites/default/files/designing_freedom.pdf (p. 11) [Accessed 19 October 2015]

[6] Phillips, M. (2014) ‘Agile + R&D: A Match Made in Heaven?’ Project Manager Today, Vol XXVI Issue 4 (May 2014), pp. 24-26

[7] DSDM Consortium (2008) DSDM Atern Pocketbook, White Horse Press, Whistable, p. 35 (4th ed)

[8] Charles Caleb Colton (1780-1832), English cleric, writer and collector, famous for his many aphorisms

No comments:

Post a Comment