Further posts will explore VSM’s sub-systems in more detail, with relation to project management.

For those who wish to follow up on VSM in more detail, there are some references at the end of this post.

Systems (the S of VSM)

The word system is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as “a set of things working together as parts of a mechanism or an interconnecting network; a complex whole”. In a sense a system is an oxymoron because there is no such thing as “a system” since everything in existence is in some way interconnected. However for convenience, we break down this mega-system into smaller systems with artificially defined boundaries. Thus the United Kingdom is a system within which Local Government exists as smaller governing systems. A local government body will be further sub-divided into functional systems such as education, highways, and so on.The great systems thinker Donella Meadows wrote that "that a system must consist of three kinds of things: elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose" in her book Thinking in Systems. The elements are the easiest part of a system to define as they are the bits that are visible. Interconnections are less visible so harder to define - they are essentially how the elements communicate so that they are part of the same system - in the human body, for example, nerves are one of the elements, and nerve impulses travel along the nerves to do things like register heat or pressure. Finally there is purpose, which can be the most difficult to define. For example, an alien visiting earth and seeing an old people's home might decide that it's purpose is to kill people since everyone who goes there dies.

A system’s boundaries are also permeable: for example the allocation of responsibility between central government and local government changes over time.

In project management terms, a project is a system that has been consciously created to fulfill a specific purpose. But like all systems, it exists within a Russian doll model of higher and lower level systems. The “permeable boundary” of a project is seen in terms of changes in project scope and also where project outputs become embedded in business as usual.

Viable Systems Model (VSM)

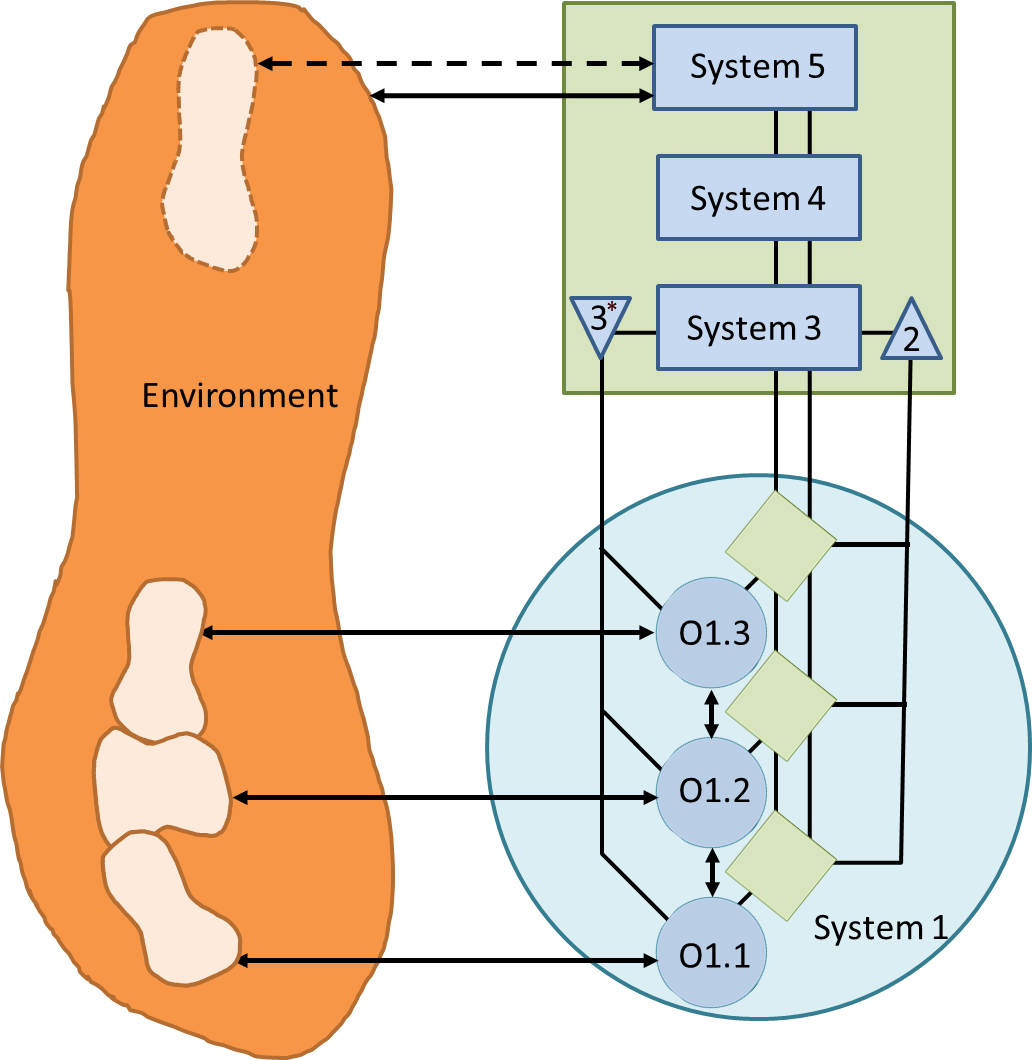

The VSM is a model (a representation) of a system that is viable (i.e. that is capable of survival). It is based on the real-life VSM of the human autonomic system “the part of the nervous system responsible for control of the bodily functions not consciously directed, such as breathing, the heartbeat, and digestive processes” (OED) and also of the higher level brain functions. In other words, it’s a model for how the human body controls what it does in a meaningful way that enables the brain to concentrate on higher level functions without having to bother about all the necessary, life sustaining things that also have to be done.It is also a fractal or recursive model. In other words it’s like the Russian dolls referred to above. It describes the current system, but also higher and lower level systems.

The model has five main parts:

System 1: Operations

This is the part that does a specific function such as making the heart beat. Each system will have many operational units, each with their own separate purposes, but all interacting in some way to drive the system as a whole.System 2: Local regulatory

In human body terms, this is the sympathetic autonomic nervous system that ensures that the system 1 components interact in a stable manner. An example of instability is where one operation is out of kilter with another: for example running up a hill and getting out of breath because the need for oxygen supply outstrips the lungs’ ability to provide it.System 3: Local feedback

In the human body this is the parasympathetic nervous system. System 2 is responsible for maintaining stability of the operational units, but on its own this won’t work because it needs a higher level function that tells it what to do based on the feedback it’s getting across all the operations. This is the job of system 3 (shown as 3* on the diagram). System 3 is also the interface to the higher level functions – it filters out all the masses of information that is generated, and only passes on what matters, so that the higher level systems can take executive action if needed. (For example, telling the body to stop running up that hill!)Another function of Systems 3 is to issue instructions about changes in operations. The system has a plan, e.g. “run to the top of the hill”. So the body sets off and, as in the example above, starts to get out of breath. System 2 passes this information up to system 3, and system 3’s job is to analyse this feedback and alter the plan if necessary. For example, if we’re getting too out of breath we must stop or risk damage. That’s what system 3 decides. Stafford Beer called it the “big switch” because it’s the arbiter between letting the operations get on with what they are doing without interference… or stepping in to change things.

System 4: Adaptation to a changing environment

Let's imagine that you're running up that hill and because you're fit, you're not getting out of breath. However the radio that you're listening to on your MP3 player gives a weather report to say that there's a storm coming. So you decide to look for shelter. What has happened? You have had input from your environment, and as a result have changed your plans. Now there is the immediate environment that needs to be monitored (this is done by System 1: e.g. it's getting steeper so you need to increase effort) and there is the wider environment including what might happen in the future. The weather report is of this latter form, and it's System 4's role to scan and analyse the environment in order to provide this input for the system to decide if any changes are needed. But it's not System 4 that makes the decision...System 5: Policy

Why are we running up a hill in the first place? Maybe it’s because we need to see what’s going on around us and need that vantage point. This is the job of the brain: to take in information from the environment, analyse the state of the body, and decide on actions (i.e. set the policy). To work effectively it needs to know enough about the state of the system so that it can make appropriate decisions, but not be overwhelmed by information. Because of system 3’s filtering activity, only the important, relevant information is passed on. And because of System 4 information about the environment is provided.Going back to our running scenario, let’s say that the brain has set this in motion not because we just want to get a good vantage point, but because it has seen that there is a life-threatening danger and we have to run away from it (up the hill).

So when system 3 “decides” to slow down when we’re getting out of breath, it passes on the situation to the brain (system 5) which says “no, don’t stop”, over-riding system 3’s normal response. So system 3 passes that back and we keep on running!

Stafford Beer drew a diagram based on the human model, and the five systems are shown on it, as illustrated here (click to enlarge). A peculiarity of the diagram is that the overall shape of the whole system – a circle topped by a square – is replicated by the individual operational units (labelled O1.1, O1.2 and O1.3). This is where recursion comes in because each operational unit is itself a system so has the same 5 sub-system structure within.

Project management and VSM

If you’re familiar with PRINCE2 and similar project management approaches you’ll know that there is usually a project governance set-up (a board with sponsor and other senior stakeholders), a project manager and a project delivery team. Mapping this onto the VSM diagram the delivery team is clearly System 1 and the board is System 5. The project manager role is System 3 and if we have delivery team leaders they might be acting in a systems 2 role (but as we’ll see, possibly not fulfilling it very well). Where is System 4?Even at this superficial level, the VSM model shows gaps in the way an organisational system is set up. And as we shall see in later posts, other gaps become apparent when you look at the systems in more detail.

But let’s return to the missing system 4 – what is missing exactly? In a well run project team leaders (System 2) will be proactive in terms of monitoring how their operations (System 1) are going. Where there are inter-dependencies between the operations, they will communicate to make sure things are joined up. If any issues arise, they can feedback on them both to the other operations and to the project manager (System 3). The project manager is aware of all the feedback coming in from all the operations (via their System 2s) and can send back appropriate inhibitors (recall that System 3 works out whether parts of System 1 are over-stressed). If the issues in System 1 are beyond the “autonomic” control capability, in theory System 3 should pass this information to System 5 where decisions will be made that combine the top level policy requirements and the stability needs of the system to make appropriate adjustments. If the adjustments seem too large then System 5 can be altered to make a policy decision (e.g. agree a scope change, delay, overspend, etc.). This seems like the project manager’s job as well.

Interestingly enough, in programme management, there is the notion of a business change manager/leader who works alongside the programme manager. It seems to me this is more like the System 4 role (with programme manager as System 3), which is manifestly missing in the project management system.

In the next part I’ll look more closely at the workings of system 1: the operational units.

References:

Beer, S. (1981) Brain of the Firm; Second Edition, John Wiley, London and New York.Beer, S. (1988) The Heart of Enterprise; (reprinted with corrections), John Wiley, London and New York

Espejo, R. and Harnden, R. (eds) (1989) The Viable System Model; John Wiley, London and New York.

Hoverstadt, P. (2008) The Fractal Organization: Creating sustainable organizations with the Viable System Model, John Wiley, London and New York

Meadows, D.H. (2009) Thinking in Systems, Earthscan, London and Sterling VA

Walker, J. (2006) The VSM Guide. An introduction to the Viable System Model as a diagnostic & design tool for co-operatives & federations [online] Available from: http://www.esrad.org.uk/resources/vsmg_3/screen.php?page=home (accessed 3 Oct 2013)

Great! I loved the read. I used to underestimate the importance of having a good erp tailored to my company's needs - now that I have microsoft dynamic I can really tell the difference.

ReplyDelete